How to choose and care for a secure open source project

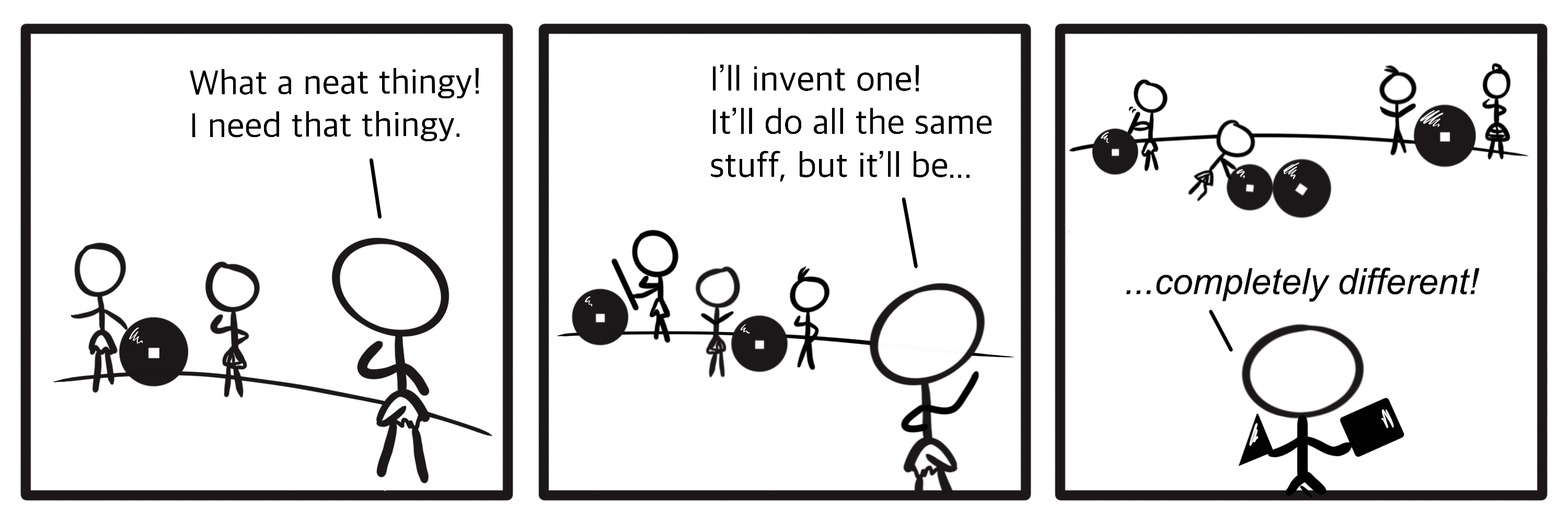

How to choose and care for a secure open source projectThere is a rather progressive sect of the software development world that believes that most people would be a lot happier and get a lot more work done if they just stopped building things that someone else has already built and is offering up for free use. They’re called the open source community. They want you to take their stuff.

Besides existing without you having to lift a finger, open source tools and software have some distinct advantages. Especially in the case of well-established projects, it’s highly likely that someone else has already worked out all the most annoying bugs for you. Thanks to the ease with which users can view and modify source code, it’s also more likely that a program has been tinkered with, improved, and secured over time. When many developers contribute, they bring their own unique expertise and experiences. This can result in a product far more robust and capable than one a single developer can produce.

Of course, being as varied as the people who build them, not all open source projects are created equal, nor maintained to be equally secure. There are many factors that affect a project’s suitability for your use case. Here are a few general considerations that make a good starting point when choosing an open source project.

How to choose an open source project

As its most basic requirements, a good software project is reliable, easy to understand, and has up-to-date components and security. There are several indicators that can help you make an educated guess about whether an open source project satisfies these criteria.

Who’s using it

Taken in context, the number of people already using an open source project may be indicative of how good it is. If a project has a hundred users, for instance, it stands to reason that someone has tried to use it at least a hundred times before you found it. Thus by the ancient customs of “I don’t know what’s in that cave, you go first,” it’s more likely to be fine.

You can draw conclusions about a project’s user base by looking at available statistics. Depending on your platform, these may include the number of downloads, reviews, issues or tickets, comments, contributions, forks, or “stars,” whatever those are.

Evaluate social statistics on platforms like GitHub with a grain of salt. They can help you determine how popular a project may be, but only in the same way that restaurant review apps can help you figure out if you should eat at Foo’s Grill & Bar. Depending on where Foo’s Grill & Bar is, when it opened, and how likely people are to be near it when the invariable steak craving should call, having twenty-six reviews may be a good sign or a terrible one. While you would not expect a project that addresses a very obscure use case or technology to have hundreds of users, having a few active users is, in such a case, just as confidence-inspiring.

External validation can also be useful. For example, packages that are included in a Linux operating system distribution (distro) must conform to stringent standards and undergo vetting. Choosing software that is included in a distro’s default repositories can mean it’s more likely to be secure.

Perhaps one of the best indications to look for is whether a project’s development team is using their own project. Look for issues, discussions, or blog posts that show that the project’s creators and maintainers are using what they’ve built themselves. Commonly referred to as “eating your own dog food,” or “dogfooding,” it’s an indicator that the project is most likely to be well-maintained by its developers.

Who’s building it

The main enemy of good open source software is usually a lack of interest. The parties involved in an open source project can make the difference between a flash-in-the-pan library and a respected long-term utility. Multiple committed maintainers, even making contributions in their spare time, have a much higher success rate of sustaining a project and generating interest.

Projects with healthy interest are usually supported by, and in turn cultivate, a community of contributors and users. New contributors may be actively welcomed, clear guides are available explaining how to help, and project maintainers are available and approachable when people have inevitable questions. Some communities even have chat rooms or forums where people can interact outside of contributions. Active communities help sustain project interest, relevance, and its ensuing quality.

In a less organic fashion, a project can also be sustained through organizations that sponsor it. Governments and companies with financial interest are open source patrons too, and a project that enjoys public sector use or financial backing has added incentive to remain relevant and useful.

How alive is it

The recency and frequency of an open source project’s activity is perhaps the best indicator of how much attention is likely paid to its security. Look at releases, commit history, changelogs, or documentation revisions to determine if a project is active. As projects vary in size and scope, here are some general things to look for.

Maintaining security is an ongoing endeavor that requires regular monitoring and updates, especially for projects with third-party components. These may be libraries or any part of the project that relies on something outside itself, such as a payment gateway integration. An inactive project is more likely to have outdated code or use outdated versions of components. For a more concrete determination, you can research a project’s third-party components and compare their most recent patches or updates with the project’s last updates.

Projects without third-party components may have no outside updates to apply. In these cases, you can use recent activity and release notes to determine how committed a project’s maintainers may be. Generally, active projects should show updates within the last months, with a notable release within the last year. This can be a good indication of whether the project is using an up-to-date version of its language or framework.

You can also judge how active a project may be by looking at the project maintainers themselves. Active maintainers quickly respond to feedback or new issues, even if it’s just to say, “We’re on it.” If the project has a community, its maintainers are a part of it. They may have a dedicated website or write regular blogs. They may offer ways to contact them directly and privately, especially to raise security concerns.

Can you understand it

Having documentation is a baseline requirement for a project that’s intended for anyone but its creator to use. Good open source projects have documentation that is easy to follow, honest, and thorough.

Having well-written documentation is one way a project can stand out and demonstrate the thoughtfulness and dedication of its maintainers. A “Getting Started” section may detail all the requirements and initial set up for running the project. An accurate list of topics in the documentation enables users to quickly find the information they need. A clear license statement leaves no doubt as to how the project can be used, and for what purposes. These are characteristic aspects of documentation that serves its users.

A project that is following sound coding practices likely has code that is as readable as its documentation. Code that is easy to read lends itself to being understood. Generally, it has clearly defined and appropriately-named functions and variables, a logical flow, and apparent purpose. Readable code is easier to fix, secure, and build upon.

How compatible is it

A few factors will determine how compatible a project is with your goals. These are objective qualities, and can be determined by looking at a project’s repository files. They include:

- Code language

- Specific technologies or frameworks

- License compatibility

Compatibility doesn’t necessarily mean a direct match. Different code languages can interact with each other, as can various technologies and frameworks. You should carefully read a project’s license to understand if it permits usage for your goal, or if it is compatible with a license you would like to use.

Ultimately, a project that satisfies all these criteria may still not quite suit your use case. Part of the beauty of open source software, however, is that you may still benefit from it by making alterations that better suit your usage. If those alterations make the project better for everyone, you can pay it back and pay it forward by contributing your work to the project.

Proper care and feeding of an open source project

Once you adopt an open source project, a little attention is required to make sure it continues to be a boon to your goals. While its maintainers will look after the upstream project files, you alone are responsible for your own copy. Like all software, your open source project must be well-maintained in order to remain as secure and useful as possible.

Have a system that provides you with notifications when updates for your software are made available. Update software promptly, treating each patch as if it were vital to security; it may well be. Keep in mind that open source project creators and maintainers are, in most cases, acting only out of the goodness of their own hearts. If you’ve got a particularly awesome one, its developers may make updates and security patches available on a regular basis. It’s up to you to keep tabs on updates and promptly apply them.

As with most things in software, keeping your open source additions modular can come in handy. You might use git submodules, branches, or environments to isolate your additions. This can make it easier to apply updates or pinpoint the source of any bugs that arise.

So although an open source project may cost no money, caveat emptor, which means, “Jimmy, if we get you a puppy, it’s your responsibility to take care of it.”